Part 2 of 2 in a series on curbside management strategies and why cities need one

In Part 1, we explored how the curbside has evolved from a traditional zone of parked cars into one of the most contested spaces in the transportation network. We highlighted the practice of a Curbside Management Strategy (CMS) as a way to assign curb space intentionally, instead of leaving it to chance, money, or whoever shows up first.

But even a great strategy doesn’t mean much if it sits in isolation. For curbside planning to work, it needs to be integrated into how cities plan, design, and deliver mobility. Here’s where that needs to happen.

Curbside Strategy Belongs in Every Transportation Plan

Cities already build detailed long-range transportation plans, climate action plans, equity frameworks, and infrastructure strategies. Yet far too often, the curb is left out – or worse, assumed to be static.

That approach creates disconnects between what cities say they value (like safety, equity, or multimodal access) and how they actually manage space on the ground.

A good CMS can bridge that gap – and it should be embedded into the following key planning and engineering tools.

Transportation Master Plans (TMPs)

TMPs are where cities set long-term goals for walking, cycling, transit, and vehicle movement. But without curbside policies, these plans risk being aspirational but unimplementable.

Curb allocation is where those mode priorities become real. For example, if a TMP wants to prioritize cycling on certain corridors, the CMS should support that by removing conflicting curb uses (like loading or long-term parking). This can also be ‘enforced’ by having City Council adopt these curbside principles.

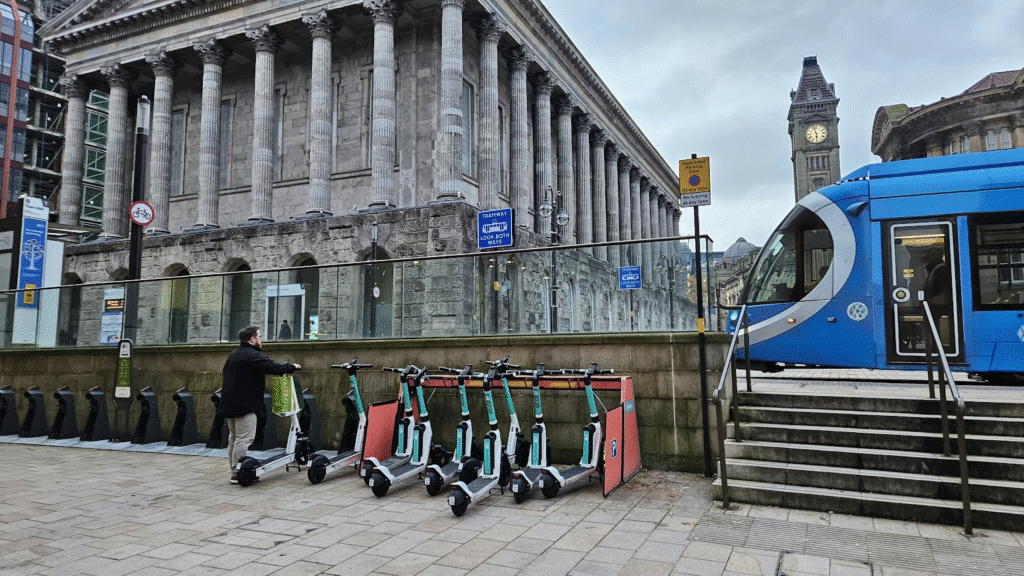

Mobility Hubs and Station-Area Plans

These areas are meant to support high-frequency transit and seamless connections between modes but they often suffer from unmanaged curb use. You can’t talk about first/last mile access without thinking about curb space for loading, bikeshare, carshare, or accessible pick-up.

A CMS helps define what access means, who it serves, how it functions block by block, but also how it holistically is incorporated into the broader (curbside) network.

Complete Streets and Vision Zero Initiatives

Making streets safer isn’t just about protected lanes – it’s about managing the curb to reduce conflicts. Think about visibility at intersections, school drop-offs, and delivery activity in bike lanes. Curb management directly affects all of these.

A CMS provides the policy support needed to design streets that are safe, not just theoretical. This can include placing the right curb functions or uses on the right streets and corridors, the minimize conflicts, and separate uses and travel modes where appropriate and viable.

Transportation Demand Management (TDM)

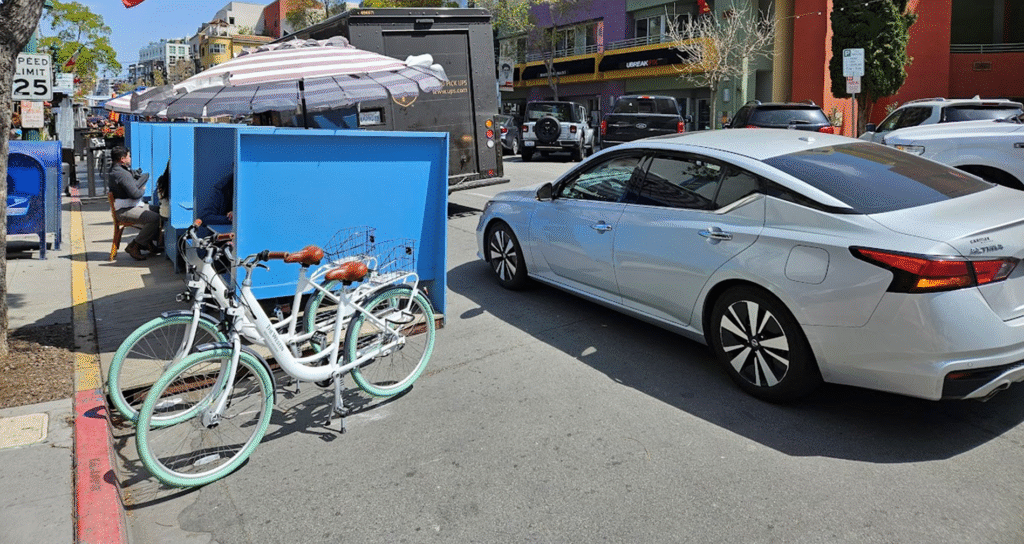

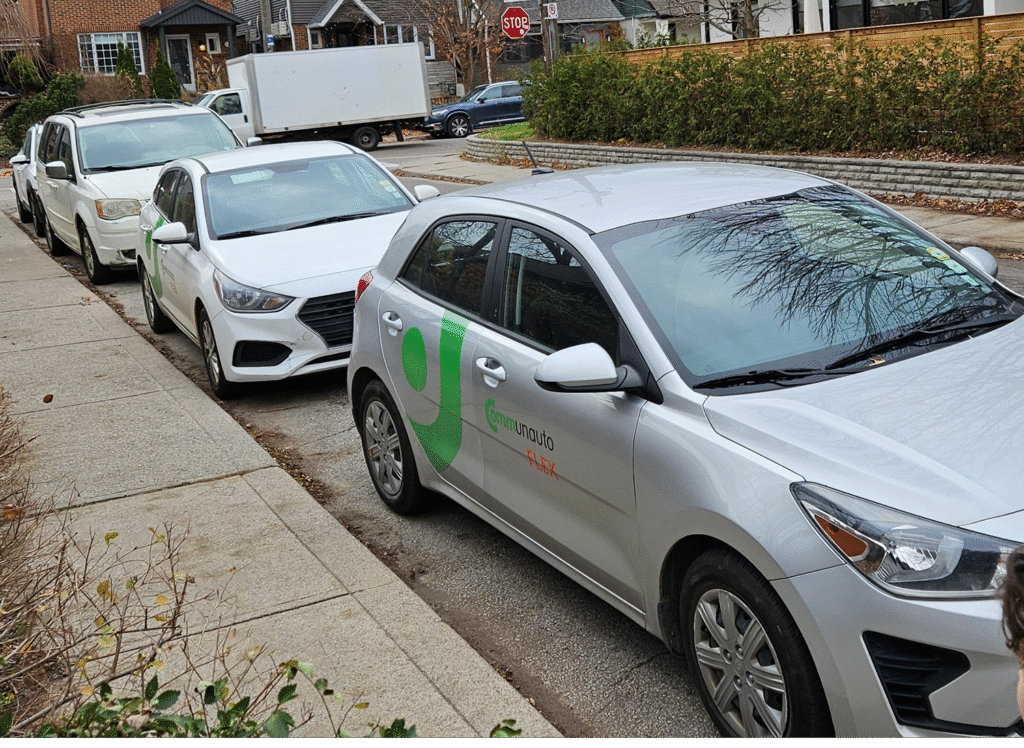

TDM aims to reduce single-occupancy vehicle trips by offering better alternatives. But those alternatives, like carshare, micro-transit, or bike parking, all need space at the curb. A CMS makes sure the physical environment supports behavioural change. As before, it can help provide policies and principles that encourage or even mandate the holistic view of the curbside, to purposely plan for dedicated or flexible space for these uses.

So Why Now?

Because curb space is increasingly scarce, valuable, and political.

As cities densify and transportation modes diversify, the curb becomes a site of trade-offs. Trade-offs between freight and pedestrians, between parking and patios, between safety and throughput. If we don’t plan for those trade-offs explicitly, we end up with a mess of signs, paint, complaints, and inefficiencies.

By including curbside strategy in mainstream planning and engineering, cities can:

- Reduce friction between users

- Align space allocation with policy goals

- Create equity environments

- Support digital tools and dynamic pricing

- Prepare for future demands, from automation to climate adaptation

A Final Word

You’ve probably heard the phrase: “You can’t manage what you can’t measure.” That’s especially true for the curb.

But I’d add this: You can’t plan for the future of mobility if you don’t include the edge of the road.

This starts by not just treating the curb as leftover space but starting to treat it as the valuable, flexible, city-shaping tool it is. It is perhaps the most important part of urban mobility today, so let’s make sure it is captured in future transportation plans.